A History of the 12th Evac Hospital

A History of the 12th Evac Hospital

By Stuart M Poticha MD., Capt. US ARMY 1966-1968

Photos by John P Nelson DDS

The long and storied history of this extraordinary hospital began on December 23, 1917, when it was first constituted as Evacuation Hospital Number 12 and organized at Fort Riley Kansas. The hospital was sent to France where it participated in the St. Mihiel Campaign of World War I. After the war the hospital was deactivated, but was reconstituted in 1925 as the 12th Evacuation Hospital in the organized reserves. In 1942, shortly after the onset of World War II, the unit was ordered into active military service and was reconstituted as a 750-bed hospital primarily staffed with doctor and nurse volunteers from the Lennox Hill Hospital in New York City. On January 5, 1943, after staffing and training was completed, the entire hospital along with 47 officers 52 nurses and 318 enlisted men, was loaded aboard the Queen Elizabeth and sent to sea, destination unknown. The Queen traveling alone at high speeds zigzagged her way across the Atlantic until she was joined January 12th by an escort of ships and Spitfires who guided her into harbor at Greenock, Scotland.

The 12th Evac was set up in a series of six tented hospitals in Southern England, Most of their patients were air force casualties incurred in the Battle of Britain, Their mission changed drastically on June 6, 1944, when the hospital began receiving casualties from the Normandy beaches, After treating 8,000 patients during its stay in England. The 12th was assigned to General Patton’s 3rd Army. At 750 beds, the 12th was the 3rd Army’s largest evacuation hospital and it accompanied Patton’s army as they raced across France and Germany.

The tented hospital was often situated as close as 2 miles from the front and the hospital moved forward as the front lines advanced, The 12th treated over 8,000 patients in the Battle of the Bulge, The hospital was in Frankfurt, Germany, at the end of the war in Europe and was being reorganized to be shipped to the Pacific when World War II ended, The 12th had cared for over 26,000 casualties while on the continent.

The story of my service with the 12th Evacuation Hospital began in 1966, I had completed a five-year residency in General Surgery at Northwestern University Medical School in Chicago in June 1965, I was appointed to the surgical faculty and was beginning my surgical practice. One afternoon, as I was finishing rounds, I was paged with a phone call. When I picked up a phone, I heard someone say, “Dr. Poticha, this is Colonel (so and so, I have forgotten or more likely repressed the name) I just wanted to tell you that you are going directly to Vietnam. Don’t bring your family, don ‘t bring your car and don ‘t bring any personal belongings because you are going from basic directly to Vietnam!” “Wait a minute,” I said, “You must have the wrong number I’m not even in the army.”

“Oh, you haven’t received your draft notice yet? Well, that will come tomorrow, but you are going directly to Vietnam. Goodbye.”

That was my introduction to the United States Army!

All drafted physicians were sent to Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio for their basic training. So, in February 1966, I arrived at Fort Sam along with several hundred other drafted young docs to learn how to become an Army officer and a battlefield surgeon. Most of basic training was conducted in lecture halls and was directed at teaching us how to become Army officers. As new draftees, we had to learn the basics such as which uniform was appropriate at which time, how and where to attach patches, badges and bars, who and how to salute, and how to march and how to give orders to troops on a march. We even were taught to shoot and had to qualify with rifle and .45-pistol. The Army realized that we were all physicians who knew how to care for patients, but there were a few specialized medical lectures on the diagnosis and treatment of tropical diseases with strange names such as Dengue Fever, Leptospirosis, Tsutsugamuchi fever and, of course, malaria.

Civilian surgeons who had trained in large cities were familiar with the management of gunshot wounds usually from small caliber pistols. Now we were being trained to deal with the high velocity missiles of war. I remember watching high-powered rifles being shot into blocks of gelatin to show us the wide spread damage that this ballistic energy caused to solid tissue.

We were taught the importance of recognizing and excising devitalized tissue in order to prevent infection and a new principle for treating highly contaminated wounds. Instead of closing wounds after they were cleansed the skin was left open. This allowed the human body’s remarkable repair mechanisms to push to the surface any remaining foreign material or dead tissue. After 48 hours, the wounds were again cleansed and the skin closed. This technique called delayed primary closure markedly reduced the number of infections and saved many lives in Vietnam.

Most importantly, it was in basic training that the 25 or so physicians and surgeons who would form the nucleus of the 12th Evac first came together. Every evening we gathered to tell stories of civilian lives, our training, our families and, of course, to bitch about the Army. The camaraderie that began at Fort Sam served us well in the coming months in Vietnam. We became a cohesive unit, a dedicated band of docs who could put our egos aside and work together to provide the best possible care for the wounded Soldiers we were soon to encounter.

Once basic had been completed we were all sent to Fort Ord, a sprawling base on the Pacific, south of San Francisco. We were advised not to bring our families since we would be leaving shortly for Vietnam. A few military exercises were conducted in the remote hills of Fort Ord. Once we had to set up the entire hospital as would have been done in WW II when the front lines changed. However, because of our supposed imminent departure, we could not be given permanent assignments in the base hospital, operating rooms or clinics and most of the physicians had little to do during the weeks we languished at Fort Ord.

A different story was enfolding for the enlisted men of the 12th. They spent their time inventorying and packing an entire 400-bed hospital with all its equipment supplies and tented housing into an innumerable number of huge steel Conex containers. Finally, after some four months and numerous false alarms, on August 28, 1966, all of the personnel of the 12th Evac in full field uniforms were loaded onto buses and delivered to the Port of Oakland where to the rousing music of a naval band we boarded ship for our seventeen day voyage to Vietnam.

The USNS Edwin E. Patrick was a troop transport ship commissioned in January 1945. She was capable of transporting 5,217 troops and all their equipment, but on this voyage, there were only about 2,000 on board. The ship held an extensive medical dispensary that included a fully equipped operating room. Beside . the usual shenanigans that took place as we . passed the International Date Line and were initiated into King Neptune’s Court and the Royal Order of the Golden Dragon, the voyage was memorable for two other events. First, our two-day passage through a Pacific typhoon that caused most of us to be so sea sick that we weren’t even able to move from our bunks, and secondly, an emergency appendectomy I performed aboard ship. Technically the first operation of the 12th Evac’s Vietnam history was a simple appendectomy.

The ship anchored off Quy Nhon, Vietnam, and we got our first taste of war. That night the sky was alight with the fire of explosions somewhere on shore. Streaks of red fire emerging from unseen gunships added to the display. Little did we know then that we would be experiencing the same fiery scenes nightly for the next year, only then the explosions would be much closer. The next morning the ship left Quy Nhon and headed south to Vung Tau, where all the medical personal were off-loaded on LST’s and driven ashore. Even though we were advised that Vung Tau was safe, all were apprehensive when the boats grounded, the front ramps dropped down, and we waded ashore.

All the medical officers were flown to Long Bien. Apparently, the exercises for moving the hospital as the front lines changed weren’t going to be applicable. In Vietnam, there were no front lines. Instead a fixed building hospital was being constructed which was not completed and the doctors were being sent to other locations in Vietnam. I was sent to the Central Highlands, first to An Khe and later to Pleiku. We had occasional casualties to treat at both of those surgical hospitals, but nothing like the mass casualty days we were about to see in Cu Chi.

By 1966, the Army was gearing up to send large numbers of ground troops to Vietnam. They had already come to the realization that this was going to be a different type of war. There were no constantly shifting front lines. The various fighting units were assigned to an area where they created a secure home base and from there were sent out to search and destroy the enemy.

The base camp of the 25th Division was at Cu Chi in the Province of Hau Nghia. Part of our base was built over an extensive tunnel system that was used regularly by the Viet Congo Cu Chi was located about 45 kilometers northwest of Saigon, about midway to the Cambodian border. We were surrounded by the Ho Bo Woods, rubber plantations and just to the east the infamous Iron Triangle. The base was a large area cleared of all tropical growth and rubber trees and surrounded by rows of barbed wire interspersed with armored vehicles. Within this camp, the 12th was assigned a square section of real estate bordered on one side by a battery of 175mm artillery, on a second side by the base fuel dump, and on the third and fourth sides by Division headquarters and communication center. This site had been the location of a much smaller hospital, the 7th MASH, that we were to replace.

Although the medical staff had been farmed out to various hospitals across the country, the construction engineers and our enlisted men were busy laying the cement pads and constructing the 54 Quonset type building that formed the hospital. The design of the hospital itself was two parallel rows of buildings separated by about fifty yards of dirt that in the rainy season turned into a gigantic mud pit that could only be crossed by two covered wooden sidewalks. The first row of building fronted the helipad and contained emergency pre-op, radiology, two operating room buildings and three intensive care units. All these Quonset type buildings were airconditioned. The OR buildings each contained three small operating rooms separated from each other by curtains. The second row of buildings housed the post-op recovery units and the medical wards.

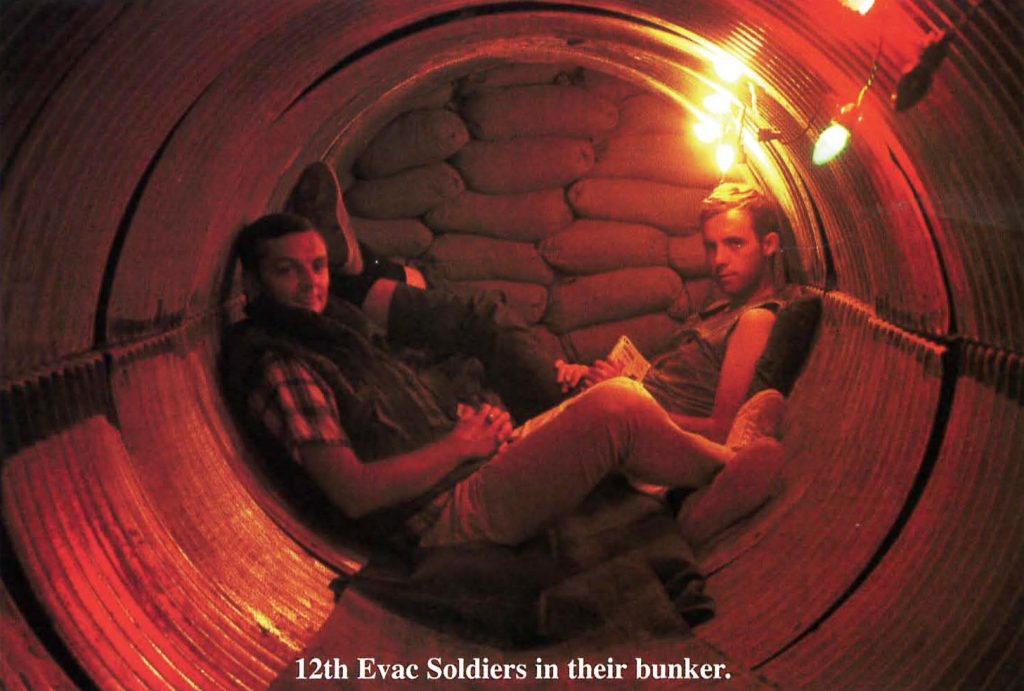

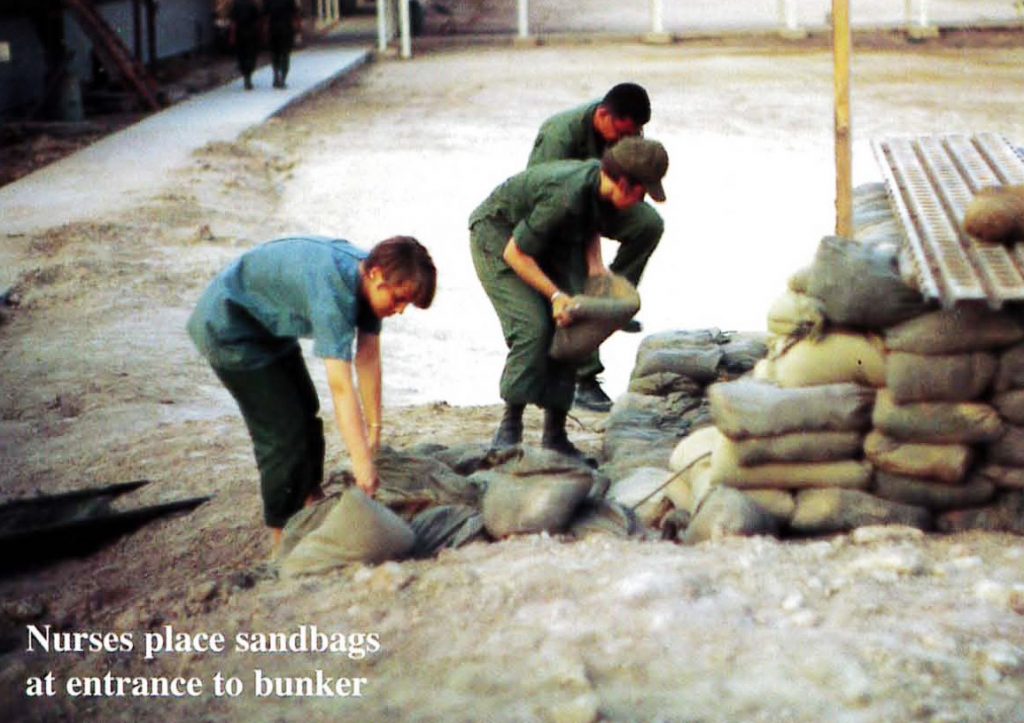

The doctors and officers were housed in hooches with wooden floors and wooden sides extending upward about 4 ft. Above that were screens and the whole structure was covered with a canvas tent. Each of the three hooches housed ten cots, five on either side of an aisle that ran down the center of the tent. We partitioned our hooch so that each officer had a tiny private space adjacent to his cot, but others kept the whole space open. Between each of the hooches we built our sandbagged rocket and mortar shelters. In late November, all the physicians were recalled to Cu Chi and the nurses arrived. We received our first casualties on December 4, 1966. The remaining days were a mixture of frantic activity interspersed with long days of boredom. When a helicopter landed, patients were rushed by stretcher to the pre-op hut where clothes were cut off. As the patients were examined the severity and location of the wounds was assessed, transfusions and respiratory resuscitation started and superficial hemorrhage was controlled. Some wounds were horrendous, beyond description. Those patients who were unstable were immediately taken to the ORs. Others were sent to x-ray first.

At times, there were two choppers on the ground unloading patients and several others circling. In mass casualty situations, we might have 50, 60 who knows how many arriving at once. The base itself was frequently attacked by mortar and rocket fire . When that happened, we rushed to the shelters and as soon as the noise stopped, we ran to pre-op. In mass casualty situations, extra tents were hastily erected around the helipad and these served as extra ER’s and resuscitation centers. Lieutenant Colonel Andy Rusinko, who was Regular Army and the second in command, walked among these wounded men doing triage. Although I was usually operating on patients, on a few occasions, I had to do the triage and I felt the enormity of that task. Walking down the rows of desperately wounded men, with a glance and cursory exam deciding who would go to surgery first and who could wait for the next available operating room. It was the hardest job I ever had.

Surgeons worked continuously until all had been cared for, sometimes over 24 straight hours. Patients with massive bleeding from shattered liver or spleens, torn great blood vessels and even penetrating wounds to the heart were saved. If they got to the hospital alive, our job was to make sure they left alive.

Although huge amounts of blood were needed, unlike civilian hospitals, there was never a shortage of blood. Some patients had their entire blood volume replaced several times until the hemorrhages could be stopped. Every time a call went out that blood was needed a long line of volunteers from 25th Division immediately formed. When the blood reached the operating rooms it was still warm.

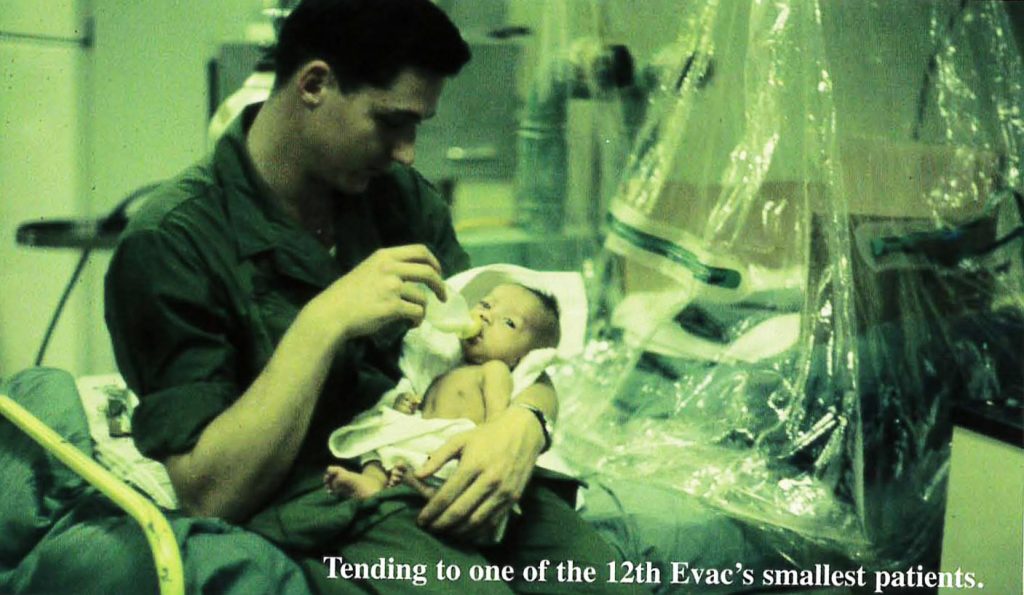

The 12th Evac ended its mission in Vietnam in 1970. During its four years of service we treated over 37,000 patients. The 12th entered the history books having treated the most patients with the lowest mortality rate of any hospital in Vietnam.

The history of the 12th Evacuation Hospital does not end with its service in Vietnam. The hospital was reactivated to serve in the wars of the Middle East, but that is another story to be told by another author. After the hospital completed its mission in Vietnam, a group headed by LTC Dick Harder formed the 12th Evacuation Hospital Vietnam Association. Dr. Jeriel Beard started a newsletter that was published yearly and sent to all association members. In 1970, the first reunion of the 12th was held in Nashville. Every five years another reunion was held, usually in San Antonio. Andy Rusinko had retired in San Antonio and he always held a big party for the 12th during the reunion. These reunions were a wonderful time to resume old friendships and relive old memories. In 1970, Dick led a group of the 12th alumni on a return trip to Vietnam . Our last reunion was held in 2011.

We have chosen this year to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the 12th’s service in Vietnam. We have joined the reunion of the 25th Infantry Division Association to be held in Virginia Beach, Virginia, September 8-14, 2019. In addition to the activities planned by the 25th, we will be holding a special event for the 12th on Friday, September 13. We have reserved a meeting room where we can all gather, share photos and memories. What a wonderful chance to see old friends, share your stories and just reminisce.

Registration forms and details about the reunion can be found in the winter and spring editions of ‘Flashes’ (the magazine of the 25th Infantry Division Assn.) or on their website www.25thida.org under the heading Reunions.

If you have any questions or comments you’d care to share please feel free to contact me at mendrps@yahoo.com.

Come and join us.

Thanks to Edward V Grant & LTC Dick Harder for contributing to this article